Emancipation movie: The true story of ‘Whipped Peter’ in Will Smith’s new film

A photograph of an enslaved man who survived a whipping that left his body mutilated and scarred helped to reveal the brutality of American slavery. Actor Will Smith stars in Emancipation, a film that recounts the story of “Whipped Peter” and his journey from slave to soldier.

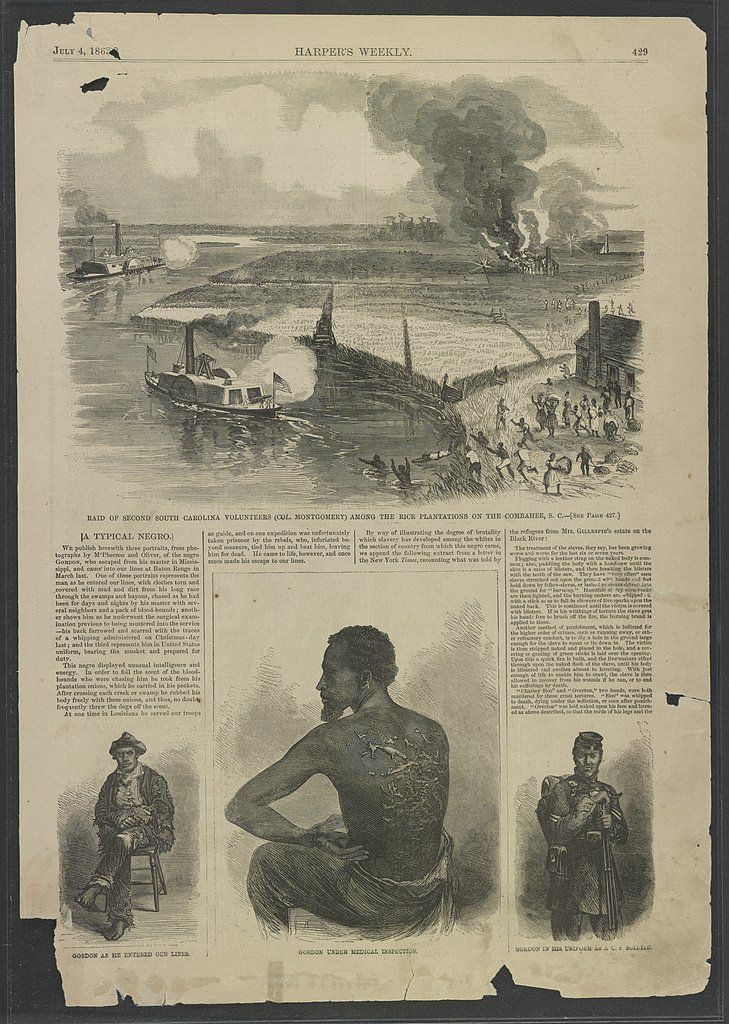

Though his skin had been flayed open dozens of times by the sting of a whip and then painfully scarred over, Gordon, an escaped enslaved man, posed defiantly for a portrait in 1863.

At the height of the US Civil War – when facts about the horrors of slavery were often decried as false propaganda – the gruesome photograph revealed the undeniable truth.

Abolitionists dubbed the man in the photo “Whipped Peter”, and while historians have debated his real name, there is little doubt about the impact his image had on the American psyche.

The photograph showed “these were real people with real experiences. It was taken to present a visual narrative of the horror of slavery during the Civil War,” said Barbara Krauthamer, a leading historian of US slavery and emancipation, and Dean of the College of Humanities and Fine Arts at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

“What often gets lost is the focus on the man himself – the story of this man who understands that the Civil War is an opportunity to literally take ownership of his body and his life.”

Will Smith’s film Emancipation is inspired by the true story of Gordon/”Whipped Peter” and directed by Antoine Fuqua. Smith told reporters at the film’s premiere that he hopes the movie will reveal the power of the human spirit.

“This is not another slave movie. This is a freedom movie,” Smith said. “I think it’s a story that we all need to see, hear and feel.”

A harrowing escape

In April 1863, mere months after enslaved people were declared free by the Emancipation Proclamation, Gordon stumbled into a Union soldier encampment just outside Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

Exhausted, near-starving, and wearing only rags, Gordon broke down at the sight of the freed black soldiers who were fighting to end slavery in America, according to a December 1863 column in the New-York Daily Tribune. He immediately asked to enlist.

During a medical examination, Gordon told officers he decided to escape after surviving a brutal whipping that left him near death and in a coma for two months. After 10 days of being chased through the Louisiana swamps and bayous by bloodhounds and slave catchers, Gordon finally made it to the Union encampment and freedom.

He then revealed his “scourged back” as proof. Photographers embedded with the soldiers took the now infamous photo of Gordon posed, bare-backed with his hand on his hip.

The Tribune notes the sight of his mutilated body “sent a thrill of horror to every white person present, but the few blacks who were waiting … paid but little attention to the sad spectacle, such terrible scenes begin painfully familiar to them all”.

According to the National Gallery of Art, one New York journalist remarked that the image should be “multiplied by 100,000 and scattered over the States”.

And that’s exactly what happened.

The horrors of slavery go viral

Gordon’s portrait was taken at a time when the country was debating whether the war effort was worth it, and if black men – enslaved or freed – should be allowed to enlist as soldiers.

In their book, Envisioning Emancipation: Black Americans and the End of Slavery, Prof Krauthamer and her co-author, photography historian Deborah Willis, describe how advances in photography enabled the image of Gordon’s whipped back to be affordably reproduced on small notecards and shared widely.

Abolitionists sold reprints of his image to raise money for their efforts. But, Prof Krauthamer said, reactions to the portrait were mixed.

“It was entirely common for people to say, it’s fake, I don’t believe it,” she said. “White people did not think black people were reliable witnesses, even to their own experiences.”

On 4 July 1863, the popular magazine Harper’s Weekly reprinted an etching of Gordon/”Whipped Peter” alongside images of Gordon in Union uniform. The accompanying article was headlined “A Typical Negro” and described Gordon’s harrowing escape from slavery and valiant record of service in the Union army.

Even for an article that was anti-slavery, historians have noted the undertones of racism as the writer takes pains to describe Gordon’s “unusual intelligence and energy”.

‘Whipped Peter’s’ legacy

The Civil War was the first conflict to be documented through photography – but very few pictures capture the horrors and the brutality of slavery as clearly as the image of “Whipped Peter”.

Though his images became an effective tool for anti-slavery messaging and propaganda, Prof Krauthamer said very little is known about Gordon’s life and legacy after joining the Union Army.

“There’s an argument to be made, that [the portrait] was just another way of objectifying a black body,” she said, adding that modern-day discussions about Gordon’s portrait underscore the power of photography to document the truth.

Less than a century after Gordon’s portrait was taken, Emmett Till’s mother, Maime, held an open casket funeral after her son was brutally kidnapped, tortured and lynched because, in her words: “I wanted the world to see what they did to my baby.”

That photo of Till’s mutilated body also shocked the American conscience and revealed the enduring legacy of racism in the United States.

Prof Krauthamer said that as a historian, she tries to centre not just the pain but also the joy of the black American experience in her work.

“I think much of the scholarship has sort of focused on ‘what’s the true story?’ And I just want to know, what was his life like? Who did he love? What did he hope to achieve?”

“My hope is that that’s what the Will Smith movie and this photograph opens a portal on to – our ability to imagine that story and that humanity.”

- 2 October 2019