Life after Daft Punk: Thomas Bangalter on ballet, AI and ditching the helmet

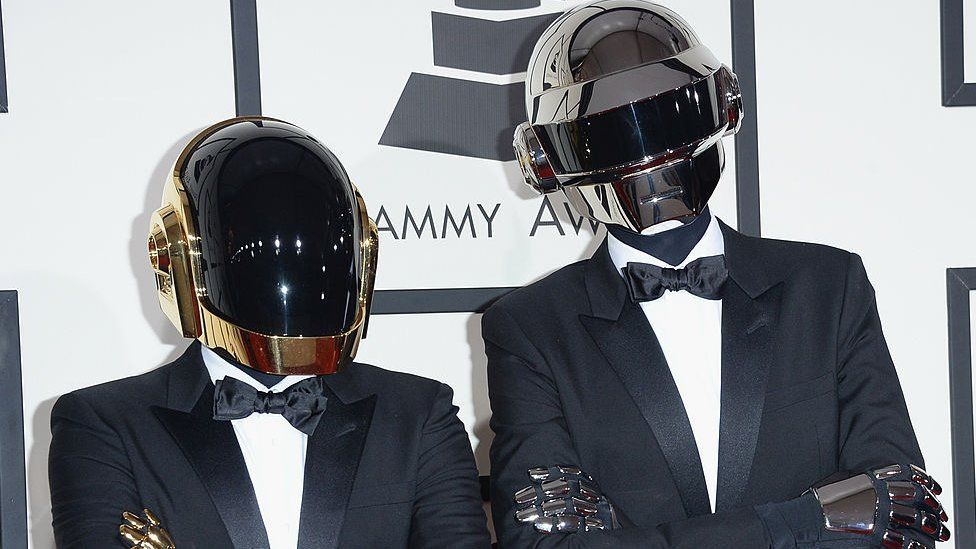

For 28 years, Daft Punk blurred the lines between man and machine on hits like Da Funk, One More Time and Get Lucky. Now, as he turns his hand to ballet, one of the duo has a warning about Artificial Intelligence and the “obsolescence of man”.

By the time Daft Punk broke up in 2021, Thomas Bangalter and Guy-Manuel de Homem-Christo had irrevocably changed the sound of modern pop.

Everyone from Madonna to Kanye West copied their chopped and filtered house sound. They were (inaccurately) blamed for the rise of disposable Euro-dance. And then, in a typically audacious move, they went analogue.

Released in 2013, their final album, Random Access Memories was a lush, colourful tribute to the soul, disco and soft rock they’d been raised on. Built from the ground up with live musicians, it won the Grammy for album of the year.

And then, they just stopped.

The band announced their split with a typically enigmatic video. Dressed as the two robot characters they’d inhabited since 1999, Bangalter and de Homem-Christo waved goodbye, walked off screen, and one of them self-destructed. Daft Punk, their publicist confirmed, were over.

So what next?

For Bangalter, the answer lay in his childhood.

His mother and his aunt were both dancers, and his uncle a dance instructor. So when France’s foremost contemporary choreographer, Angelin Preljocaj, asked him to score a new ballet, the answer was simple: Yes.

“This project was a way back to the environment I was presented with when I was very young,” he explains.

“My mother passed about 20 years ago and going back to that world is linked to a certain time of my life. So it adds some nostalgia, but at the same time, it was a very new adventure.”

Mythologies, which premiered last July in France, brings together dancers from the Ballet Preljocaj and the Opéra National de Bordeaux, telling stories from ancient folklore, from Icarus and Zeus to Aphrodite and the Amazons.

Combining the approach of the two ensembles – one classical, the other contemporary – the aim is to explore how historic conflicts over gender identity, sexual violence and war continue to have repercussions today.

The concept would seemingly demand a score that mixed ancient and modern approaches. Preljocaj, who had used Daft Punk songs in previous shows, certainly thought so. But Bangalter had other ideas.

“I liked the idea of writing music that was not amplified, that didn’t require any electricity,” he says. “It was just me and the scoring paper.”

Work started in 2019, only to be interrupted by Covid-19.

“It was somehow lockdown-compatible as a process,” says Bangalter, who used the extra time to embark on a “crash course in orchestration”.

“The first step was to read orchestration treatises from Rimsky-Korsakov or Berlioz and understand the rules I wanted to follow and to not follow and to break. It was a very humbling process, for sure.”

The structure of the ballet helped. Instead of a long symphonic work with distinct movements and motifs, Mythologies works almost as a pop album, with 16 separate “frescos”, each requiring its own musical setting.

Les Amazones, for example, is a rhythmically playful workout for the strings; while Minotaure prowls around the orchestra with sinister, tremoring bass notes from the cellos and the brass.

“As a novice, I liked the idea of eclecticism and variety, and having freedom in the overall structure,” he says.

Although he’d written for an orchestra before, notably on the soundtrack to 2010’s Tron: Legacy, some of Bangalter’s ideas didn’t make sense when presented to the players.

“The nature of what I was asking them to play, sometimes even in terms of the management of their breath, was not practical.”

Conductor Romain Dumas would advise when he’d overstepped the mark. “Then I’d have to go back and find a new solution,” he says. “As a process, it was just fascinating.”

Bangalter channelled that learning into a piece called L’Accouchement, or childbirth. Rather than draw on his experiences as a father (he has two sons with French actress Élodie Bouchez), he made it a meditation on the creative process.

“It’s something with a lot of tension that somehow leads to a peaceful moment of happiness. This was a good metaphor for how I approached this project, when I was a little bit scared.”

Writing in isolation, Bangalter often had no idea of how the choreography was progressing, making rehearsals a revelation.

“My favourite moment was seeing what had been a very solitary process of many months in my study, leading to 55 musicians performing the music and 20 dancers on stage.

“It was amazing to witness living theatre again, after this moment of separation and solitude.”

Reviews, however, were mixed.

The “chiselled, intense, and hard-hitting” choreography is illuminated by Bangalter’s “nervous” but “lyrical” score, wrote Amaury Jacquet in Publikart.

Radio France was less impressed, describing the music as “a bad Hollywood soundtrack at worst, rhythmic orchestral pop at best”.

No, no, no, it was “beautiful and flawless,” argued Guillaume Monnier in Le Bonbon Nuit. However, he added, “the music does not seem to want to stand out from the dance… Too contemplative, perhaps?”

Listeners can make their own decision when the music is released by Erato/Warner Classics this Friday. Divorced from the ballet, you can hear echoes of Vivaldi, Monteverdi, American minimalism and film composers like Bernard Herrmann, while Daft Punk’s wit and warmth percolates beneath the surface.

Coincidentally, the album is coming out at the same time as a 10th anniversary edition of Random Access Memories, stuffed with outtakes and demos. Among them is a fascinating, fly-on-the-wall recording of Bangalter and US singer Todd Edwards writing Fragments of Time in the studio.

“It’s fun because it was quite unexpected,” says Bangalter. “Todd and I weren’t aware the engineer was recording the session, so we were able to be very spontaneous.”

In the audio, the duo freestyle over the music, trading ideas as the song takes shape. When Edwards sings, “Faces that I’ve seen in dreams“, Bangalter suggests the more impressionistic, “Familiar faces I’ve never seen“. Edwards is so taken with the line that he starts giggling. After that, the song almost writes itself.

“It was a beautiful moment… very joyful.”

The decision to peel back the curtain could only have been taken after the band’s demise, he says.

“Daft Punk was a project that blurred the line between reality and fiction with these robot characters. It was a very important point for me and Guy-Man[uel] to not spoil the narrative while it was happening.

“Now the story has ended, it felt interesting to reveal part of the creative process that is very much human-based and not algorithmic of any sort.”

That was, he says, Daft Punk’s central thesis: That the line between humanity and technology should remain absolute.

“It was an exploration, I would say, starting with the machines and going away from them. I love technology as a tool [but] I’m somehow terrified of the nature of the relationship between the machines and ourselves.”

He talks as a debate rages over the use of Artificial Intelligence in music creation. David Guetta has called it “the future” while Nick Cave says it’s a “travesty”. Where does Bangalter fall?

“My concerns about the rise of artificial intelligence go beyond its use in music creation,” he says, suddenly serious.

“2001: A Space Odyssey is maybe my favourite film and the way [Stanley] Kubrick presented it is so relevant today – because he is asking exactly the question that we have to ask ourselves about technology and the obsolescence of man.”

That’s always been his position, he stresses. It’s just that people sometimes misinterpreted Daft Punk’s aesthetic as an unquestioning embrace of digital culture.

“I almost consider the character of the robots like a Marina Abramović performance art installation that lasted for 20 years,” he says.

“We tried to use these machines to express something extremely moving that a machine cannot feel, but a human can. We were always on the side of humanity and not on the side of technology.”

That’s why 2021 was the right time to pull the plug on the project.

“As much as I love this character, the last thing I would want to be, in the world we live in, in 2023, is a robot.”

- 22 February 2021

- 28 June 2013